Here's a quick note to remind me how I setup a WSL shell in ConEmu.

I just created a new task with the following command:

set PATH="%ConEmuBaseDirShort%\wsl";%PATH% & wsl

Simple as that.

Here's a quick note to remind me how I setup a WSL shell in ConEmu.

I just created a new task with the following command:

set PATH="%ConEmuBaseDirShort%\wsl";%PATH% & wsl

Simple as that.

Here's a quick note to help if you have issues installing the Windows Subsystem for Linux, specifically the following error:

"WslRegisterDistribution failed with error: 0xc03a001a"

I was trying to install Ubuntu 20.04 LTS on Windows 10 Home (10.0.18363) following the instructions found here:

There are several posts out there that can help:

For me the solution was simple, I navigated to the %LOCALAPPDATA%/packages/ folder and located the Ubuntu distribution package.

Figure 1 - Locate the package

Right-click on the package and select General > Advanced. Uncheck "Compress contents to save disk space".

Figure 2 - Uncheck "Compress contents to save disk space"

Now relaunch the Linux distribution from the store. Everything should now work.

Be aware, this blog post contains my notes on some investigation work I recently undertook with MassTransit, the open source service bus for .Net. The code contained herein was just sufficient to answer some basic questions around whether a MassTransit-based endpoint could be hosted in a .Net Core 3.1 Worker Service running on Linux.

NB: This is all “hello world” style code so don’t look here for the best way to do things.

My objectives were:

This step turned out to straightforward. Again, to reiterate my approach almost certainly isn’t best practice but served only to demonstrate the feasibility of the approach.

I created a Worker Service using Visual Studio and adapted the template project to suit. First up I installed a few NuGet packages to enable MassTransit using AWS SQS transport, and support for dependency injection. I also added support to deploy the Worker Service as a systemd daemon.

I was then able to configure the MassTransit bus using dependency injection. However, I chose not to start the bus at this point but rather use the Worker Service lifetime events to do that (described later).

public class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

var host = CreateHostBuilder(args).Build();

var logger = host.Services.GetRequiredService<ILogger<Program>>();

logger.LogInformation("Responder2 running.");

host.Run();

}

private static IHostBuilder CreateHostBuilder(string[] args) =>

Host.CreateDefaultBuilder(args)

.UseSystemd()

.ConfigureServices((hostContext, services) =>

{

services.AddHostedService<Worker>();

services.AddMassTransit(serviceCollectionConfigurator =>

{

serviceCollectionConfigurator.AddConsumer<Request2Consumer>();

serviceCollectionConfigurator.AddBus(serviceProvider =>

Bus.Factory.CreateUsingAmazonSqs(busFactoryConfigurator =>

{

busFactoryConfigurator.Host("eu-west-2", h =>

{

h.AccessKey("xxx");

h.SecretKey("xxx");

});

busFactoryConfigurator.ReceiveEndpoint("responder2_request2_endpoint",

endpointConfigurator =>

{

endpointConfigurator.Consumer<Request2Consumer>(serviceProvider);

});

}));

});

});

}

Note that I setup a simple message consumer which would respond using request response, just for testing purposes.

public class Request2Consumer : IConsumer<IRequest2>

{

private readonly ILogger<Request2Consumer> _logger;

public Request2Consumer(ILogger<Request2Consumer> logger)

{

_logger = logger;

}

public async Task Consume(ConsumeContext<IRequest2> context)

{

_logger.LogInformation("Request received.");

await context.RespondAsync<IResponse2>(new { Text = "Here's your response 2." });

}

}

For the purposes of this example I chose to use the Worker Service hosted service lifetime events to start and stop the MassTransit bus. Rather than inherit from the BackgroundService base class – which provides an ExecuteAsync(CancellationToken) method which I didn’t need – I inherited directly from the IHostedService and used the StartAsync(CancellationToken) and StopAsync(CancellationToken) methods to start and stop the bus respectively.

public class Worker : IHostedService

{

private readonly ILogger<Worker> _logger;

private IBusControl _bus;

public Worker(ILogger<Worker> logger, IBusControl bus)

{

_logger = logger;

_bus = bus;

}

public Task StartAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

_logger.LogInformation("Starting the bus...");

return _bus.StartAsync(cancellationToken);

}

public Task StopAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

_logger.LogInformation("Stopping the bus...");

return _bus.StopAsync(cancellationToken);

}

}

I used a separate console application (not shown here) to send messages to the Worker Service which I initially ran as a console application on Windows. That worked pretty much immediately proving that the .UseSystemd() call would noop when running in this mode, as expected. Great for development on Windows.

Running the Worker Service in Docker was also quite straightforward. I chose to use the sdk:3.1-bionic Docker image which uses Ubuntu 18.04. This choice of Linux flavour was arbitrary.

I had intended to try and get systemd running in the Docker container but I quickly realised that such an approach would run contrary to how you should use Docker. With Docker, you really want to containerise your application. Services such as systemd aren’t available to you. So, I simple invoked the Worker Service DLL with dotnet as an entry point.

# Build with SDK image FROM mcr.microsoft.com/dotnet/core/sdk:3.1-bionic AS build WORKDIR /app COPY . ./ RUN dotnet restore \ & dotnet publish ./MassTransit.WorkerService.Test.Responder/MassTransit.WorkerService.Test.Responder.csproj -c Release -o out # Run with runtime image FROM mcr.microsoft.com/dotnet/core/runtime:3.1-bionic WORKDIR /app COPY --from=build /app/out . ENTRYPOINT ["dotnet", "MassTransit.WorkerService.Test.Responder.dll"]

This worked as expected with the Worker Service responding to message sent to it by my test console application. In effect, the Worker Service was running as if it was a console application.

So, build the Docker image…

Run the container…

All looks good so use a test console application to send a message and see what happens…

Worked like a charm.

It’s worth saying up front that I found the following blog post of considerable use:

To test this out I could have spun up a Linux machine in AWS (other cloud platform providers are available) but I chose to experiment with a Raspberry Pi. Note that the code for the Worker Service was unchanged from when it was run in Docker (see above).

To run the Worker service as a systemd daemon on Linux you first need to build the application with the appropriate Target Runtime. See the following documents for more information on that:

However, being a bit lazy I chose to publish direct from Visual Studio and to copy the files to the Pi manually later. For this I selected the linux-arm runtime. Note also that to avoid installing the dotnet runtime on the devoice I chose the Deployment Mode of Self-contained.

The effect of selecting linux-arm as the Target Runtime is that there’s an extension-less binary that’s executable on Linux included in the published folder. This file is important later on when we configure systemd.

The next step is to copy the files to the target device.I copied mine to a directory called /app/linux-arm. Note that you also need to set executable permissions so systemd can run the application.

The next steps follow this post: https://devblogs.microsoft.com/dotnet/net-core-and-systemd/

My .service file looked like this:

Note that ExecStart must point at the extension-less executable created when you built the application with a Linux target runtime. As you can see, the daemon was now up-and-running.

Let’s fire a test message at it and see what happens. To monitor the log output I ran the following command: journalctl -xef.

Job done!

All objectives were met. I was able to run MassTransit in a Worker Service and to host that worker service in a Linux Docker container and as a systemd daemon on a Linux host.

If I were to add .UseWindowsService() to the Worker Service it would also be possible to host the service as a Windows Service.

I have been writing an AWS lambda service based on the Serverless Framework. The question is, how do I secure the lambda using AWS Cognito?

Note that this post deals with Serverless Framework configuration and not how you setup Cogito user pools and clients etc. It is also assumed that you understand the basics of the Serverless Framework.

Securing a lambda function with Cognito can be very simple. All you need to do is add some additional configuration – an authorizer - to your function in the serverless.yml file. Here’s an example:

functionName:

handler: My.Assembly::My.Namespace.MyClass::MyMethod

events:

- http:

path: mypath/{id}

method: get

cors:

origin: '*'

headers:

- Authorization

authorizer:

name: name-of-authorizer

arn: arn:aws:cognito-idp:eu-west-1:000000000000:userpool/eu-west-1_000000000

Give the authorizer a name (this will be the name of the authorizer that’s created in the API gateway). Also provide the ARN of the user pool containing the user accounts to be used for authentication. You can get the ARN from the AWS Cognito console.

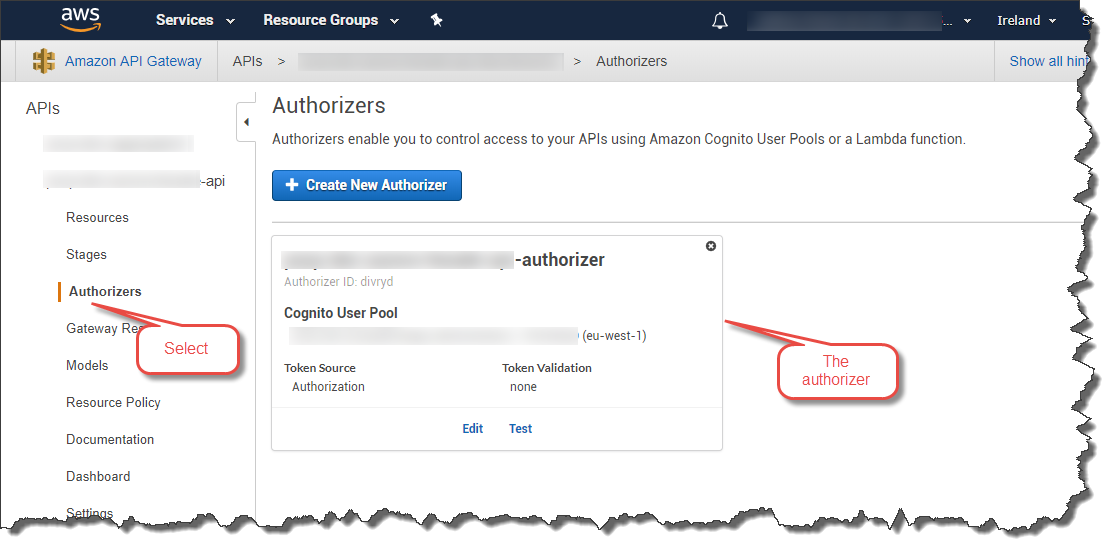

After you have deployed your service using the Serverless Framework (sls deploy) an authorizer with the name you have given it will be created. You can find it in the AWS console.

An alternative is to use a shared authorizer.

It is possible to configure a single authorizer with the Serverless Framework and share it across all the functions in your API. Here’s an example:

functionName:

handler: My.Assembly::My.Namespace.MyClass::MyMethod

events:

- http:

path: mypath/{id}

method: get

cors:

origin: '*'

headers:

- Authorization

authorizer:

type: COGNITO_USER_POOLS

authorizerId:

Ref: ApiGatewayAuthorizer

resources:

Resources:

ApiGatewayAuthorizer:

Type: AWS::ApiGateway::Authorizer

Properties:

AuthorizerResultTtlInSeconds: 300

IdentitySource: method.request.header.Authorization

Name: name-of-authorizer

RestApiId:

Ref: "ApiGatewayRestApi"

Type: COGNITO_USER_POOLS

ProviderARNs:

- arn: arn:aws:cognito-idp:eu-west-1:000000000000:userpool/eu-west-1_000000000

As you can see we have created an authorizer as a resource and referenced it from the lambda function. So, you can now refer to the same authorizer (called ApiGatewayAuthorizer in this case) from each of your lambda functions. Only one authorizer will be created in the API Gateway.

Note that the shared authorizer specifies an IdentitySource. In this case it’s an Authorization header in the HTTP request.

Once you have secured you API using Cognito you will need to pass an Identity Token as part of your HTTP request. If you are calling your API from a JavaScript-based application you could use Amplify which has support for Cognito.

For testing using an HTTP client such as Postman you’ll need to get an Identity Token from Cognito. You can do this using the AWS CLI. Here’s as example:

aws cognito-idp admin-initiate-auth --user-pool-id eu-west-1_000000000 --client-id 00000000000000000000000000 --auth-flow ADMIN_NO_SRP_AUTH --auth-parameters USERNAME=user_name_here,PASSWORD=password_here --region eu-west-1

Obviously you’ll need to change the various parameters to match your environment (user pool ID, client ID, user name etc.). This will return 3 tokens: IdToken, RefreshToken, and BearerToken.

Copy the IdToken and paste it in to the Authorization header of your HTTP request.

That’s it.

As a final note this is how you can access Cognito claims in your lambda function. I use .Net Core so the following example is in C#. The way to get the claims is to go via the incoming request object:

foreach (var claim in request.RequestContext.Authorizer.Claims)

{

Console.WriteLine("{0} : {1}", claim.Key, claim.Value);

}

This post refers to a Raspberry Pi 3b+ running Raspbian Stretch.

A quick note; I’m going to use the PuTTy Secure Copy client (PSCP) because I have the PuTTy tools installed on my Windows machine.

In this example I want to copy a file to the Raspberry Pi home directory from my Windows machine. Here’s the command format to run:

pscp -pw pi-password-here filename-here pi@pi-ip-address-here:/home/pi

Replace the following with the appropriate values:

The following example includes the –r option to copy over a directory – actually a Plex plugin – rather than a single file to the Pi.

This post refers to a Raspberry Pi 3 B+ running Raspbian Stretch.

To check that AWS Greengrass is running on the device run the following command:

ps aux | grep -E 'greengrass.*daemon'

A quick reminder of Linux commands.

The ps command displays status information about active processes. The ‘aux’ options are as follows:

a = show status information for all processes that any terminal controls

u = display user-oriented status information

x = include information about processes with no controlling terminal (e.g. daemons)

The grep command searches for patterns in files. The –E option indicates that the given PATTERN – ‘greengrass.*daemon’ in this case - is an extended regular expression (ERE).

This post covers the steps necessary to get AWS Greengrass to start at system boot on a Raspberry Pi 3+ running Raspbian Stretch. The Greengrass software was at version 1.6.0.

I don’t cover the Greengrass installation or configuration process here. It is assumed that has already been done. Refer to this tutorial for details.

What we are going to do here is use systemd to run Greengrass on system boot.

Navigate to the systemd/system folder on the Raspberry Pi.

cd /etc/systemd/system/

Create a file called greengrass.service in the systemd/system folder using the nano text editor.

sudo nano greengrass.service

Copy in to the file the contents described in this document.

Save the file.

Change the permissions on the file so they are executable by root.

sudo chmod u+rwx /etc/systemd/system/greengrass.service

Enable the service.

sudo systemctl enable greengrass

You can now start the Greengrass service.

sudo systemctl start greengrass

You can check that Greengrass is running.

ps –ef | grep green

Reboot the system and check that Greengrass started after a reboot.